Hello again, and welcome to the throng of new subscribers who’ve signed up since the new year - honestly you’ve made us very happy, and at an endlessly precarious time for culture media helped restore faith in the fact that people like proper stories and conversation (and gorgeous pictures!) as well as hype-cycle instant stimulation.

This time we’ve got someone who’s been right there at some of the most vital crux moments of modern culture and subculture, but is a perpetual outsider himself. From the day in 1974 when, while still at school in Hackney, he first photographed Bob Marley - and soon after went on the road with The Wailers - he’s produced images that embody the actual meaning of that most over-used of terms, “iconic”. His close relationship with Marley lasted until the star’s death in 1981 - and he also became in-house photographer for the Sex Pistols through the year of their greatest international fame and eventual implosion in 1977-78. He was partly responsible for immersing John Lydon in reggae when he roped him into a Virgin Records “talent spotting” trip to Jamaica, and became a vital part of Public Image Ltd, designing their logo and the (again) iconic tin packaging for the Metal Box album.

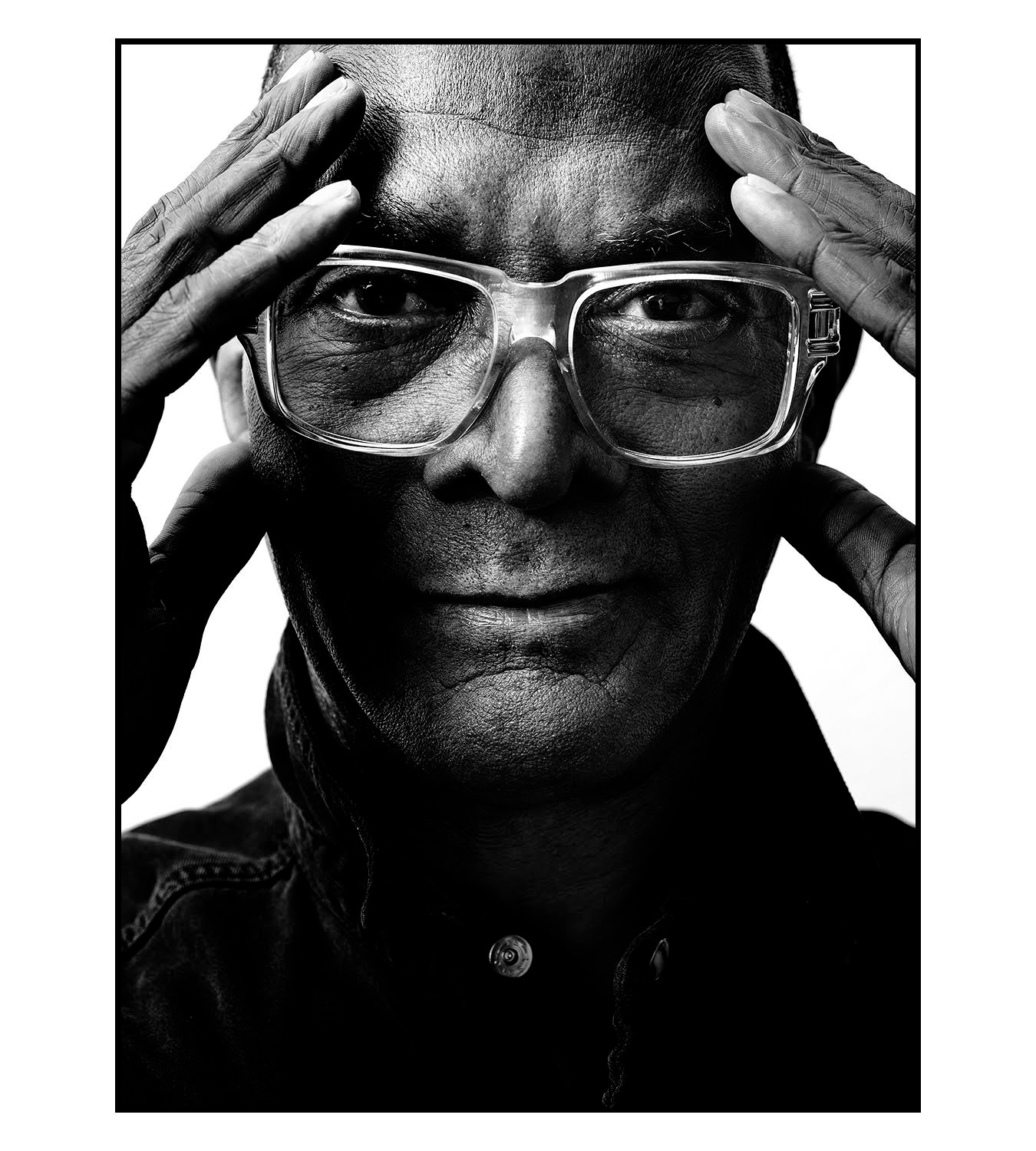

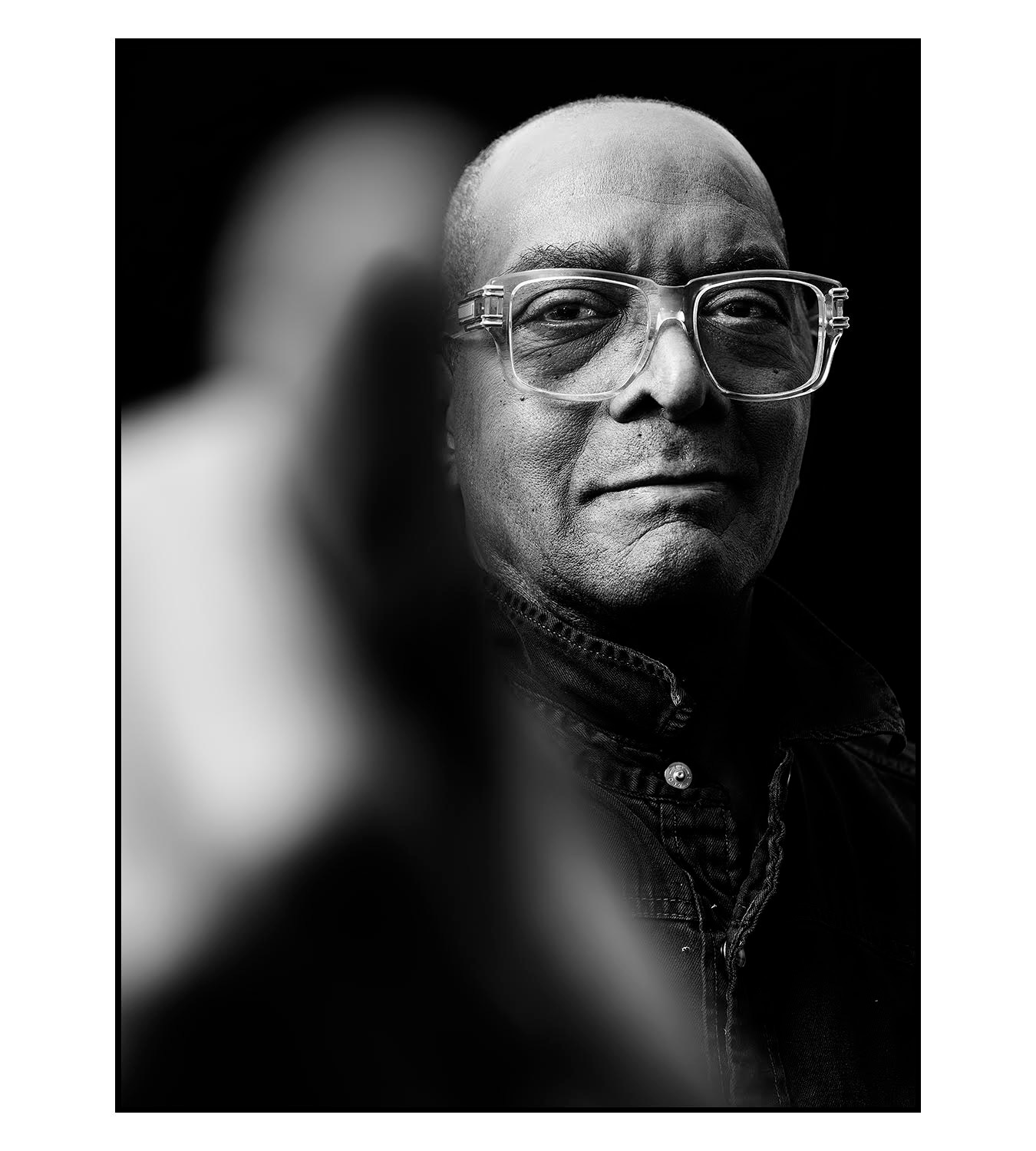

His own brief musical career was brilliant too. Replacing Donn Letts as the vocalist for Basement 5, he helped turn them into a super intense dub-punk machine, and their one and only album - produced by Martin Hannett, with drums from the Blockheads’ Charlie Charles - plus its following dub version both still slam out of the speakers with alarming force when turned up loud. It’s certainly no wonder the tracks have been picked up by hipper DJs of the NTS Radio ilk more recently, and though they were criminally ignored at the time both versions of the album were reissued in 2017. Morris’s voice is super distinctive on them too, raw and distorted but with super disciplined too, with some of the most authoritative don’t-fuck-with-me energy of any artists of the time1. And he has just the same voice and attitude now, 40+ years later: though he may not have been A Punk he is certainly Punk As Fuck. Talking on Zoom from the gallery in Burlington Street where he was overseeing the hanging of his current exhibition of Marley pictures (which is on until 7th March), with a natural instinct for a good image, he managed to instinctively frame himself full figure in his phone’s camera showing off his still-sharp style and imposingly looking down at me. His voice, at an exact midpoint between very old-school abrupt Cockney vowels and more proclamatory Caribbean pronunciation, was always exactly enunciated - and his expression (albeit punctuated with repeated “as such” “see what I'm saying to you” “in that sense” “if you understand”, which I’ve cut for clarity) was ultra clear.

As per usual for Bass, Mids, Tops and the Rest, this was less about retelling his story - which is already well documented - and more about his insights into movements he’s been adjacent to. And he didn’t disappoint, despite - or rather because of - his status as a non-joiner of tribes. We covered some extremely interesting territory particularly regarding individualist talents’ need for support networks, and the differences between American ambition and British “having a laugh” - in a perverse way, his cut-the-crap assessments he could become a successful motivational speaker if the mood took him. And there were some dryly hilarious putting in their place of some of the bigger names he’s worked with. That tough, authoritative tone can be quite forbidding at first, but actually Morris’s sharp analyses and razor wit make him great company, and this was an extremely enjoyable hour spent in conversation with him. Here he is…

So, Dennis: something fascinating you once said2 is that arriving in England as a kid, you came to understand it as much through television as via your own experiences...

That is true. Realistically, TV was my first encounters with the nature of the country. It was in some ways a window into the new world into which I'd arrived. I think with television I got a taste of English life, and it was also one of the things that influenced me into getting into photography, because I was bombarded with images...

With a frame around them!

Yeah exactly. Somehow I really took to that.

And was pop music part of that televisual education?

Yeah, sure, especially as I moved to my teen years, something like Top Of The Pops was an eye-opener to the groovy whirl of what was going on outside, the different scenarios.

Did you connect with other kids around music?

Yes and no. Realistically my school days were strange in some ways, in that I wasn't a normal regular kid into the normal regular things most of them were into. I was always into music and the visuals, the imagery around it. One of the things I always remember was striking to me was the first time I saw on Top Of The Pops Eddy Grant when he was in the band The Equals - he came on and sang “Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys” and he had an afro, but it was blonde3. I thought, “Wow” - that was out there.

I guess you were pretty young when you came over but did these pop stars contrast with what you'd seen of musicians in the Caribbean?

Pop stars didn't really exist in the Caribbean. In fact one of the biggest musics that was played in my household was country and western, in particular a guy Jim Reeves4. A lot of his songs were quite religious, I think that's maybe why, but that's one of the things that was always there. Then outside of that obviously you had calypso, ska, that kind of stuff. But to buy records was expensive, it was a luxury, so it was left to the soundsystems - that's where you'd hear your music. You'd have to be a really big music enthusiast to go out and spend your money on every new release.

Did you experience soundsystem parties from an early age, then?

Everybody within the West Indian community - every child - did. Not so much blues parties, but every wedding, christening, whatever, they'd always take their children. The kids would be in a room on the side where they could play together or whatever, but you'd hear all the music and all the commotion going on. You were never really part of it, though, unless it was a big hall in which case you'd be running around with all the people dancing and drinking. But wherever you were you were always surrounded by music in some shape or form.

So on the one hand you had this absorption of music in real life, but on the other pop stars on TV - I guess given the looks of the 60s and 70s they must have seemed quite alien compared to anything you were used to?

Well yeah. Something like glam rock, to the Black community that would be completely alien. Completely [chuckles]. But funnily enough I got into it in some ways. I don't know what it was with me but I liked the imagery. At some point I got myself a sheepskin waistcoat thing and some [really leans into pronouncing the word] boots. To most people then I looked like a complete freak, it just wasn't done.

Did you have any favourite rock stars as your tastes developed?

Oh there was all kinds of stuff coming out - I liked bands like The Sweet, and that guy, what's his name, not cool to mention nowadays?

Gary Glitter?

Yeah, obviously didn't know what we know now, but he stood out. Stuff like Marc Bolan definitely. Again, for me to be listening to that, I was listening to it literally alone. It wasn't a widespread thing in the West Indian community. It was just something I got into. Worth mentioning there was no Black radio stations at the time, so everyone listened to the same stations - and if any of the music from those artists would come, I would listen, where other Black kids of my age at the time would not even notice or bother listening to it. Their ears would only prick up if Desmond Dekker came on the radio or whatever.

And at what point did you get a sense that people banded together around music in social groups or subcultures?

Well I've spent a bit of time in America and people there find it really weird when I tell them that growing up there were Black skinheads. To a Black American, that's just like, “What?” Even for white people it's weird. They don't understand that initially it was all about the music and the style. When the Windrush movement happened we brought over style, the hats, the suits, we brought that over. White kids mimicked that. Even cutting their hair short, because at the time among West Indian people short-cut hair was popular. It's foreign to most people outside England to understand that, but skinhead at the time was just a look, it wasn't a political thing, there wasn't the racist scenario, it was about the music and the fashion - that's what it was. But whenever there's an influential youth movement, politics get hold of it one way or another.

Was that something you felt you could be part of? It's quite a way from sheepskin waistcoats...

I never felt like I could be a part of any one thing. It's like for me when it comes to clothes or fashion or whatever you want to call it, I won't wear any one label, I wear whatever I want to wear. And when it came to music my taste was always very eclectic, it was anything and everything that I liked, it's always been that way for me. Even when I worked with Bob Marley they found it weird I worked with a punk band. When I worked with Goldie later he'd find it weird I was working with so-and-so - but that's how it was, I never stayed with one movement. The biggest influence on me, or the closest thing to that sort of belonging, was working with Bob - but that was the spirituality of Rastafarianism that had an influence on me. Beyond that, no.

So something deeper and more personal than just being part of a gang...?

Well, being part of a gang you can get the same thing, you know? That's why most people join a gang, it's to be part of a family, part of a unit, part of a group. Whether it's big or small, that is deep and personal!

Did you feel like you were making a conscious decision to go your own way? Because in the 70s it almost seems like being part of a movement was the norm... certainly people were very attached to those identities.

It was just me. I was just never a joiner in any shape or form. It's how I am. I've always been a part of everything, so for example when I was working with Bob I was very conscious about what it took to be in that presence of that group of people and that movement, and to be respectful to it. I didn't go against it in any way, if you see what I mean. But at the same time there were parts of it that I felt wasn't fit for me, and I didn't want to go down the particular roads of, but there was a great deal of it I really took to. Same thing with punk: with punk there was parts of it that no way would I ever go down that road in any way - but what I did gain from punk was I learned how to literally kick the door down and take what's mine. From Bob I learned that after you've kicked the door down you need a certain spirituality and consciousness to keep things together. That's how I've always been living my life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bass, Mids, Tops and the Rest to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.