Hi everyone, welcome back. Once again, sorry for the delay: once again it’s been down to unavoidable life stuff – but we are now ready to really motor ahead. We’ve got a good few photoshoots and interviews in the can this last week, including a new generation legend of radio and clubs, our second Turner Prize winner, and coming up next our good friend, the brilliant writer Jude Rogers.

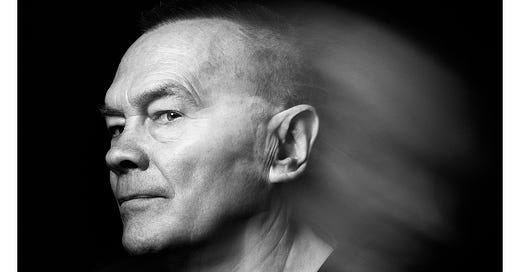

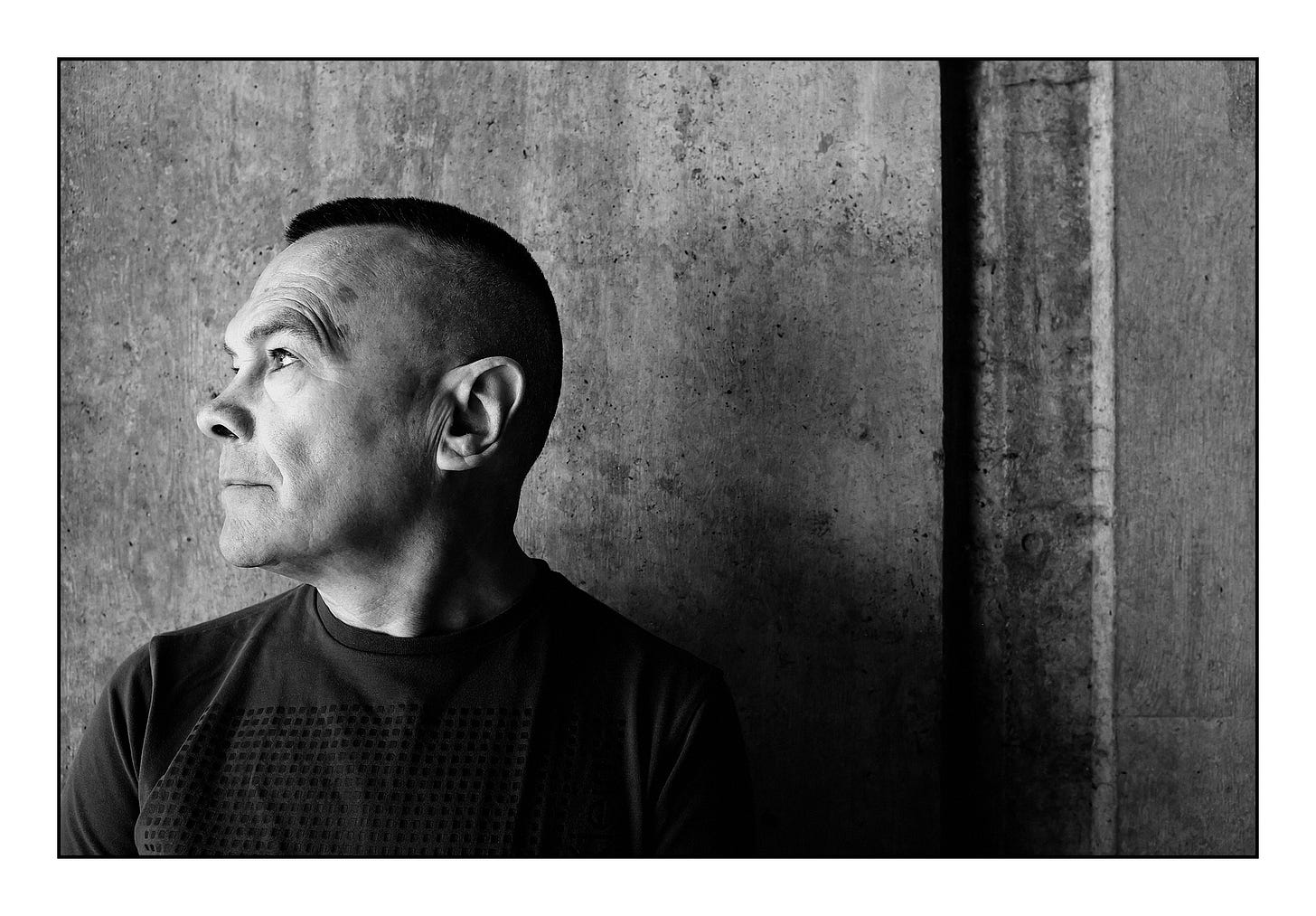

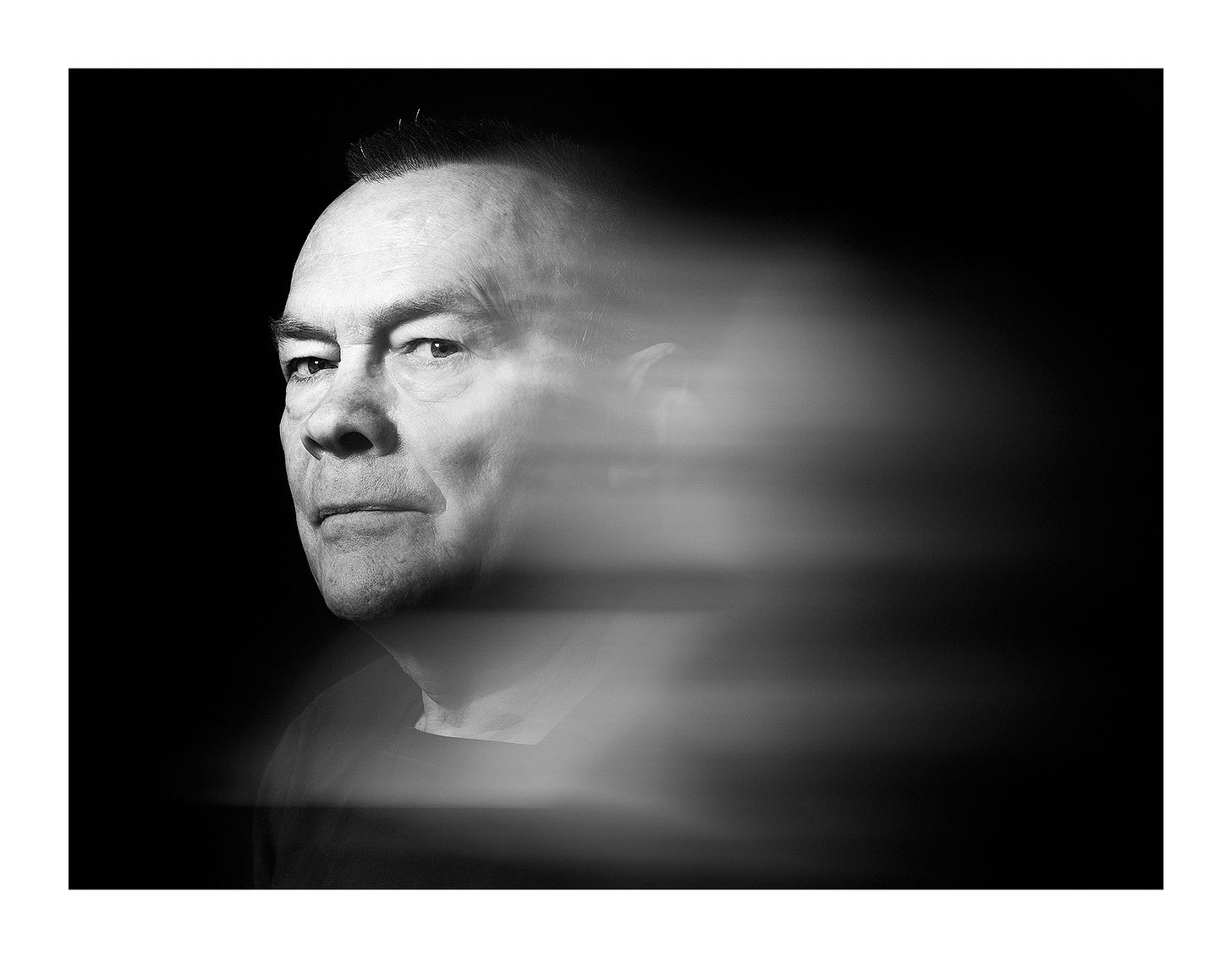

But we’re going with this one first, because, sadly, there is a sense of urgency about it. We’d always been going to include Graham Dowdall, because as you’ll see he has stories for days and an incredible, unique perspective on subcultures over the years. I first covered his work in the mid-2000s, both solo as Gagarin and duo recordings with the Iranian-Welsh singer-songwriter Roshi Nasehi1, when I had an Experimental reviews column in Mixmag – and we’d stayed in touch and on friendly terms over the years since. Brian did a photoshoot for one of Roshi and Dowdall’s releases in 2011 and likewise stayed in touch.

I guess there was a little bit of taking for granted involved, as he was someone we felt like we could call up any time rather than have to speak to PRs and what have you. However, Dowdall has been ill with cancer for a while. It seemed to be managed well, and in the past year he has recorded and released his unbelievably gorgeous Komorebi album2 and performed a load of shows – but then earlier this month it worsened suddenly, which was a really horrible wake up call that I should probably get on and interview him!

I spoke to him on Zoom from his studio in Margate, overlooking the leafy garden of the home where he’s been living with his partner for three years, after almost half a century in South London. His immediate symptoms managed, and further treatment being brought forward, he was clearly tired but pushing through: he’d had to cancel one gig, but is still planning for a live stream on the Morphic Resonance Twitch channel3 next Saturday, 25th May, and working on more music.

I would give it the big one about the incredible names Dowdall has met and work with over the years, but honestly I don’t want to spoil your read – right from the very outset, I guarantee this one will Blow. Your. Mind. We’re making this one free to read as frankly, the world needs to know more about this excellent human, and take this as a reminder to celebrate the great people in your life while they can still hear you do it

You grew up in Sussex, right? Were you born there?

No, I was born in Lewisham. Yeah. We were moved out when the North Peckham estate was built, my dad had a factory in an old railway arch. And they got moved down to Crawley New Town. But we decided not to live in Crawley New Town, we decided to live in East Grinstead, which was a good move, and a very interesting move, peculiar town. You know, I'm writing my autobiography at the moment. And we had Ron Hubbard4 for tea. We met the Church of Latter-Day Saints5 when they were building the temple. We were surrounded by Steiner people6. We were surrounded by all of that leyline weirdness stuff in a small community town.

How did the Hubbard connection come about? How did he end up at your house?

My dad was a… I mean, he's a son of Peckham. He wished he was Del Boy, he was an opportunist. They were scrap metal men who'd made a little bit good through the war with the metal trade and had a small wireworks factory that got moved down. But he'd been in the merchant navy, and he was just this opportunist with a boat fantasy. And Hubbard was very visible in East Grinstead, he would drive the Carnival Queens around in his pink Caddy. At that point, it wasn't really a religion. It was sort of a business cult. And my dad saw him on a local lake with a big speedboat and thought “Ooh, big speedboat, rich American, he's a scamster like me, but 100 times more successful. Let's inveigle ourselves.” So he started to talk to Hubbard about building a boathouse. They had this project about building a boathouse for the speedboat, which resulted in Ron coming round for tea twice.

Did you have any sense of who this was? What age were you?

I was six, maybe seven? Around that. He was famous. I knew he was a writer. I mean you'd become very aware of Scientology in East Grinstead. At that point, they were taking over primary schools and doing some very dangerous, early brainwashing stuff, sit in a room with a tomato for half an hour and don't kill the tomato, that kind of weirdness. So I knew who he was. It was pretty obvious from whether I was six, seven, or whatever I was, that this was not a spiritual person. This was a businessman and a writer. And he only turned it into a religion for tax reasons.

So you had a sense of the spiritual at that age? Were your family churchgoers?

My grandfather was a church organist and choirmaster in the Church of Scotland. And my mum took us to a Congregational church, which is a very, very low church. I was a singer, I was a boy soprano. I loved choir singing. But the religion was, it was more social than spiritual, really. There's no crucifixes in a Congregational church, there's no images of the Lord. It's very much about the parables as stories of social equality as much as anything7. But I did love the singing. Singing in a big church and the reverb and all of that stuff.

Were you tuned into sound early on then, at primary school age, do you think?

[Emphatically] Yeah. So, at three or four my grandfather let me literally walk on the bass pedals in his church, on the church organ, and the whole place reverberated in this atonal sub bass frequencies. For me, the first instrument I got into was a so called portable radio, and it's this big [holds arms out to indicate a large cabinet] and the battery was as heavy as a car radio, but on it you had short, medium and long wave, these big Bakelite dials and the names of places you've never heard of that you could tune into. But then in between all the weirdness of the old style frequencies, your long wave, your [swooping whistle] shortwave things, the number stations from Russia. I remember this weird little tune I heard forever [hums] “Boo, boo, boo, boo boo boo…” No idea where it comes from. It doesn't exist anymore. It was there every day, somewhere. I literally spent hundreds of hours on the floor dialling through this stuff. It was like a synthesiser, really, because you just click and you move and stuff like that. That more than anything stayed with me as a sort of sonic influence.

Even in the 80s it was the same, you still had these, like a barrage of medium wave and shortwave stations. And it was like an instrument, you could literally, by increasing the pressure on the knob, you could go [whistles] like a theremin.

Incredible, yeah. I mean, sadly it's gone now, pretty much. I mean I've got a shortwave radio up there [gestures towards loft], you don't get much on there anymore.

Yeah, Everything's subsumed into the fibreglass cables.

Sadly.

It's not out in the air anymore. Was there music in the house? Were your parents into music?

Yeah. Scottish folk, mostly. And then English pastoral I suppose. Benjamin Britten, Vaughan Williams, that kind of stuff really. My dad sort of affected an interest in music, but he didn't really have a lot of interest. I mean, he bought a very early Supremes. My sister was four years older than me. So when the Beatles came in 1961, she had everything. She was buying in '61, '62, '63. She was a wild child, she was a rocker. And so from the very beginning of beat music, it was in the house, alongside the pastoral and alongside the Scottish folk.

So she sort of went full-on in allegiance to that, as it were. Did you get that sense at that primary school age that this new thing was something that you could join?

Yeah, absolutely. Obviously, Elvis had been around before, but there was something about '61, '62 here where, I suppose it was ours to some extent. And Beatles culture and the other bands around that was just ubiquitous. I got given “It's All Over Now” by The Rolling Stones when I was nine. I bought “All Day and All of the Night” by The Kinks when I was nine. It was just everywhere really.

And were they resounding with you on that “I like the visceral sounds” level as well? Like, in the same way as you loved more abstract sounds? You mention The Kinks...

Oh yeah, that's where that came from. “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night”, which is where the roots of distorted guitar really lie in British terms. I suppose sonically, that was the connection point. I think culturally, Ringo Starr as a drummer was a big influence. At the age of ten I got a plastic Ringo Starr snare drum. Piece of shit. It had his face on it, it didn't sound good. I later destroyed it when I was 16 in a piece of performance art, to discover they're worth about five grand now. But I think sonically yeah, certainly The Kinks, but then of course, and I don't like to mention Margaret Thatcher8, but there was also the Joe Meek track “Telstar”. When I heard that stuff, and “Johnny Remember Me”, those kind of floaty spooky songs that really really grabbed me. “Telstar” blew my mind. Was that '64, '65 maybe?

I forget. Must be around that. Yeah.

But yeah, “Telstar”. As soon as I first heard any electronic sounds, I was excited by them, whether it came from the radio or where it came from, but they do something to me, and they did then and still do. You know, I love distorted guitar. But there's something about electronic sound that reaches a different place for me.

I remember you saying a teacher started letting you tinker around with tapes, too?

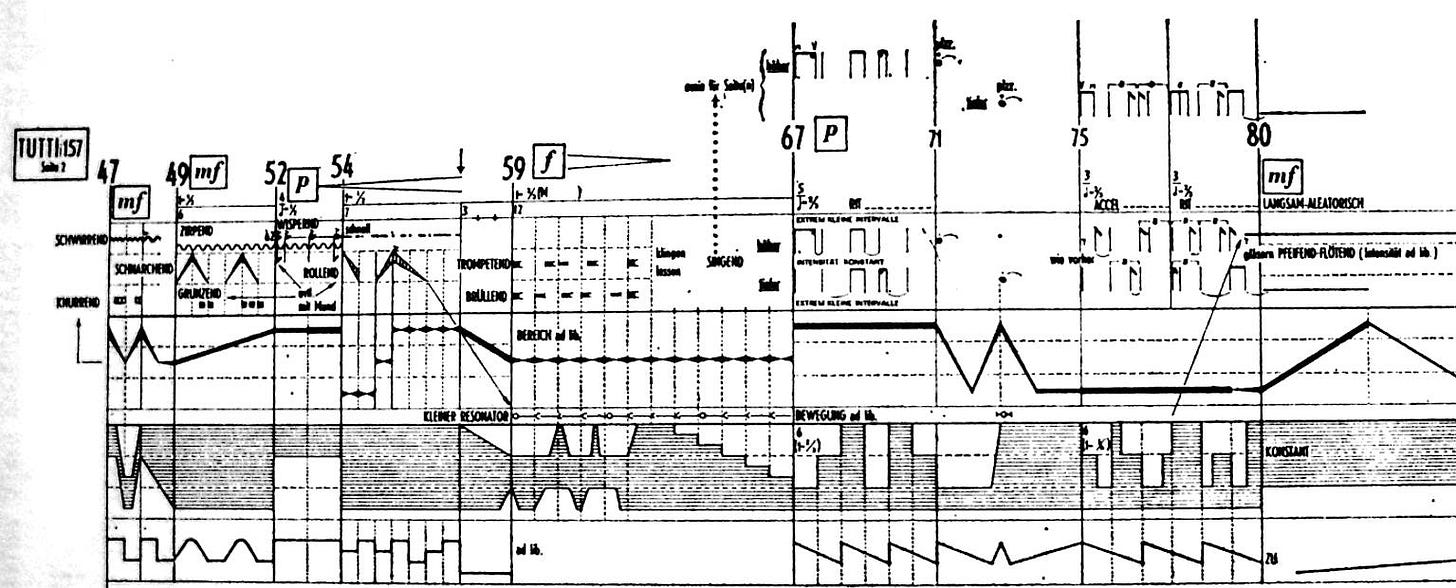

That was a little later. I was still at that point playing inside of the piano – the underneath was more interesting than the top. At my primary school, we were told to go and find something in the kitchen to make a musical instrument out of, and I got an egg slicer and was plucking that. We had an education in the early to mid-60s that was incredibly creative and incredibly liberating. The experiments with tape recording stuff came later when I was 16. I didn't do music for O level or A level, I have no qualifications. But everybody did music. Everybody did art. The music teacher bought a four-track tape recorder, editing blocks, all of that. Didn't know how to use it, didn't know anything. Gave us the tape recorder, gave us the manual, gave us a book of Stockhausen scores9, the key to the instrument cupboard, and said “Come back at the end of term with something.” So we had backward cymbals, we had tape loops, we had all of this stuff going on. We didn't know what we were doing. Before that you've got the Radiophonic Workshop. I watched the very first ever Doctor Who in 1964, and watched Doctor Who relentlessly, affected by that sound world that was completely fresh, completely new. And other BBC dramas that seemed to employ them, creating this open-mindedness to sonic adventure, that was just incredible. So before we reached tape looping ourselves, we didn't know how it was done, but that's what we were listening to.

So what year would that have been, when you were 16?

1970.

Right. So you would have heard “Revolution Number Nine” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”.

Oh yeah, all of that. And we were listening to exciting music a long time before that. The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was a big influence, The Soft Machine was an enormous influence. Kevin Ayers was an enormous influence. White Noise10, Tonto's Expanding Head Band11, the work they were doing with Stevie Wonder. All of that was going on through that gap between the beginning of my secondary school education. There was so much of it, and it was accessible. And it was accessible because you know... we were living in Sussex. We'd go up to Soho on a Saturday morning, you'd walk in a record shop and you say, “Well, we really liked the first Pink Floyd album. What else can you introduce us to?” They'd sit you in the glass box, four 13 year olds on the ground and say “Tonto's Expanding Head Band. White Noise”. And they'd just give you this stuff and leave you in there for 40 minutes.

That's a magic spot to be in.

Incredible, incredible. Those record shop guys in the early 60s, mid 60s were just so hungry to share that beautiful sound.

Yeah, and it was relatively mainstream. I mean, White Noise is quite kitschy almost.

It is kitschy, yeah! Obviously before that you had Sparky's Magic Piano12 and all of that.

Yeah, these guys were not trying to be underground, that's for sure.

No, and nor was, what was he called.... Donna Summer...

Giorgio Moroder.

Giorgio's early stuff is... I can't remember, what was his first one? Did he do “Popcorn”?

That wasn't him, that was a different German guy. But yes.

But that stuff’s cheesy, cheesy as hell. And the early Giorgio stuff is pretty cheesy, yeah.

But still with weird sounds. They still plop into those places in the brain that electronic sound does right?

Yeah, absolutely! I mean Giorgio is just an utter genius, you know, what he achieved...

And so in your mid teens did you want to be part of the gang? Did you kind of want some of that subcultural stuff?

Yeah. We started a band at 15. 1969. We, like most bands then, you do a few covers. We covered Captain Beefheart. We covered Kevin Ayers, we covered Edgar Broughton. And we did one Cream song, the first song, “Sunshine of Your Love”, that I'm sure all the kids learn first. We realised – one: we weren't very good at that, and two: we wanted to take the Beefheart, Kevin Ayers thing in our own direction. So we just started both improvising and spontaneous writing. Writing lyrics and songs at the same time was just improvising with instruments. And that's what we did from 1969 onwards really.

And did you think of that as a political act, as an anarchist kind of behaviour?

I'm not sure how political it seemed. Yeah, I guess, because the ideology of improvisation was there, and remains there really, you know, it's a challenge to everything else. The other thing to throw in there is that one of the guys, David Wickens his dad was an electronics engineer for the BBC. And he devised a tone generator, then a ring modulator, and then by 1970, he had, effectively, a modular synth. This guy was so wacky that they had a tape loop doorbell, you'd go and press the button and it would go either “You rang?” or it would be the Queen Mary arriving in Portsmouth, stuff like that.

Which reminds me, the other side of that experimentation is the Goon Show of course. That's where the Radiophonic Workshop started, and that kind of British absurdism was there in the sound experiments.

Yeah!

Did you listen to The Goon Show as a kid?

Yeah I did. I mean, I suppose that's one of the few things I got from my dad.

I had grandparents who would give me tapes of it and stuff. And obviously, some of that... it's problematic now, but the sound world was really like... it showed you that someone in a studio could put you into a weird, absurd, what you'd later understand was a kind of almost psychedelic state.

Yes, and I suppose the other thing we had very early on was the Gerry Anderson stuff. Before Supercar, there was Torchy the Battery Boy. And the other guy who could spin his arms. There was all of that, and that always had that kind of vibe going on as well really.

Yeah. And Star Trek, there were theremins galore and bleeps and the sliding doors and all of that. So, how long was it before you sort of felt that you were in a subculture? I mean, did you even, when you were in your band?

Yeah, because, you know, I'm a radical. I got very involved, very young in radical politics, and the White Panthers. I did my first free Festival in 1970. And we would put on free gigs. We just did the village hall, town hall, Crawley bandstand, we were putting on free gigs from the age of 16.

Did you feel like you were plugging into a network then? Because obviously there was the whole West London, Notting Hill, Mick Farren13 sort of thing.

Yeah. I met Mick. I met John Carding14 through the White Panthers, and of course Hawkwind. 1971. To this day, I think probably the Hawkwind gigs I saw between '71 and '73 are the most exciting live music I've ever experienced.

Very jealous. And there's more Radiophonic science fiction, right?

Oh, God, you've got these ten minute introductions of weird tone generators and stuff. And then the odd “standby for takeoff” kind of voices in the background. And then slowly these four note riffs groove in, Stacia goes off, the lights go mad, and it was just mind blowing. Just incredible.

And were you doing acid by this point?

Starting to. Yeah, I mean, we'd gotten to pot in 1970, '71. So yeah, that was all taking off.

So you were getting the full multi dimensional experience.

Yeah. Probably my best Hawkwind drug experience was with DMT. The whole audience turned into white doves. And we were just smoking while the synths were gradually building up, and then the “Master of the Universe” riff came up, and they just ripped through the sky. So intense.

You must have had a few communications with alien overlords?

I would say so, yeah.

Amazing. So did you go around free festivals?

Yeah. Windsor. Few of the other more obscure ones. I mean, I have a short attention span, so I'm not great at spending three days in a field. But a day was great.

Did you feel like a different society was being built? I mean, it was best of times, worst of times, right? A lot of bad stuff went on...

A lot of bad stuff. But a lot of good stuff, yeah. I mean, you know what it's like, that scene was like, there were people trying to build new societies. But then there were alot of hangers on, there was a lot of other more negative stuff associated with that.

Did you feel like that was where you belonged, that kind of scene? I mean, you were young, but did you think about the future and where it was going?

Yeah, I did feel I belonged. There was musically something missing there for me though. And that was the fact that in the late 60s, I got into bluebeat, ska and reggae. And that wasn't present in that world. The free festival world, at that point, was very white, and was very rock derived. And I knew my rocksteady, I knew all of that stuff in the late 60s. “Long Shot Kick de Bucket” and all that stuff just meant so much to me. The bass, the space, the lyrical stuff, the skank. And when I went to college, obviously, it was just pre disco. But I was in this weird place where I would be on a Friday night dancing to black music in a disco, and then on Saturday, getting the flares on and going off to a free festival.

Yeah, which is a kind of a balanced diet, but there's a tension between the two if they're very segregated.

And they were quite segregated. Not so much in a disco context, but beyond that, yeah.

Throughout the seventies the soulboy culture was all was there too. Was that anything to you?

Not so much, to be honest. No. For me, it was very reggae. I had a few old school skinhead mates, you know, “Skinhead Moonstomp”, and all that stuff. One of the things I loved about reggae was the freedom for men to dance on their own. That didn't really come back until rave came back. It's like, you're just there, you're just in your groove and nobody gives a damn. And so I suppose more than soulboy it was that world for me really.

Riiiiight I hadn’t thought of that but yes. Because the soul scene, even if you were dancing by yourself, it was flamboyant, it was competitive.

It was flamboyant yeah. It was white socks and flamboyant moves. Yeah, yeah. And hair down here, you know.

You discovered dub at that point as well presumably?

Yeah, I was listening to all of that. There was one night I'll never forget, I had come home from being out with the mates and we were high as kites. And I put on the transistor radio, it was probably Peel. And this music came on. And I didn't know if the music was real, if the radio was drifting off channel, or if I was so fucking high that I didn't know what was going on. And I think it was probably Augustus Pablo, or something like that. And it just blew my mind. I turned the light on and wrote everything down and that was it. That was dub for the next god knows how many years.

What about when punk came along? Was that anything to you?

Interesting, because musically, I was very much... because I was hanging around with a lot of dreads, and the dub thing was absolutely dominant. Punk came along and culturally, I felt some identification with it. But musically – as well as doing everything else, we'd go out to watch pub rock before that, '75 '74 '76. Because there was a lot of pub rock around. And to me when it first came along, punk, it was like, this is just sort of pub rock with short haircuts and narrow trousers. And it took me a while. I mean, I got the energy of the Pistols, I got the pseudo politics of anarchy. And it was exciting. But that came around the same time as “I Feel Love”. And it's like, “Oh, okay.” you know? They speak to two completely different things. Unrelated at all. But I went to see them all, I saw The Tubes, I saw Wire, I saw The Clash. I saw The Banshees and later went on to work with John15. Never saw the Pistols. The Rock Against Racism thing was an exciting move. Because you'd go and see The Clash and you'd see Misty in Roots together. And it felt like, for the first time, a coming together of the culture, then you've got 2-Tone, which was so organic in itself. And that was very exciting. Because it pulled those strands together, the punky energy and the cultural roots of reggae.

And then as it became post punk, that's kind of where you slotted in as a musician, right?

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. In 1979, when I stopped working as a lawyer16, I was working with a theatre group doing street theatre around Europe, basically doing free improvisation on the streets with surrealist clowning. Which, incidentally, got me to meet William Burroughs and Brian Gysin17 one night. So one of the performers we were working with, Professor Crump, did a clockwork plastic dog act. He was also a surrealist writer. So we got invited to this soiree. Where Burroughs did a reading, Gysin did a performance with Anthony Braxton, the sax player, and we sat and we drank wine talking to Burroughs.

Oh my god, that must have been quite something.

I couldn't believe it. I thought, I'm in a room with Burroughs and Gysin, they're doing their thing and they're talking to us.

One of the most enduring things, as far as creativity goes, that's ever lodged in my head is Burroughs, I think it was Burroughs and not Gysin, but either way it was about the cut-up technique and collage, and he said “When you cut open the past, the future leaks out.”18 And it's just like…

Yeah. Oh my God. You can go back to that stuff forever, what they opened up. In a way, particularly Burroughs because he just... [sighs] I mean, it just blows my mind still. The first time I ever heard of Burroughs... You know, our education was very liberal. We weren't introduced to Burroughs at school. We were introduced to Kerouac, so it's not a very big step. But certainly they didn't give us Wild Boys and Junky at school, but we got to it ourselves. So yeah, post punk, '79. I was doing basically industrial percussion on the street with a bunch of clowns. And I wanted to find a niche. And then I heard... actually, you know what I really heard. I heard Martin Hannett's snare sound19. That was it really I think. I mean, those records are just astonishing. And they spoke of Manchester, they spoke of the post industrial north, they spoke of electronics, they spoke of Eastern Europe too, in some way, you know. And I, by some coincidence, got the offer to go and join Ludus in Manchester.

And they were sort of semi goth adjacent as well. I guess goth and post punk, kind of. Because Youth kind of opened my eyes a little bit when he talked about how The Batcave was the birth of electronic music club culture for him20, because there were so many drum machines and stuff going on in Alien Sex Fiend and The Sisters and all of that sort of stuff.

Yeah, yeah I guess so. I mean, the thing with Ludus was sort of organic, in a way. It was mostly a three piece, we struggled to find a bass player. So I was playing kit and Syndrums, carrying huge 18 inch bass bins in order to get some sub bass out of my Syndrums. And it was a pretentious band. I mean, Morrissey was our tea boy. Literally, he made tea while we rehearsed. And it was incredibly pretentious. Linder, the singer, went on to be a very, very successful artist.

Incredible artist, yeah.

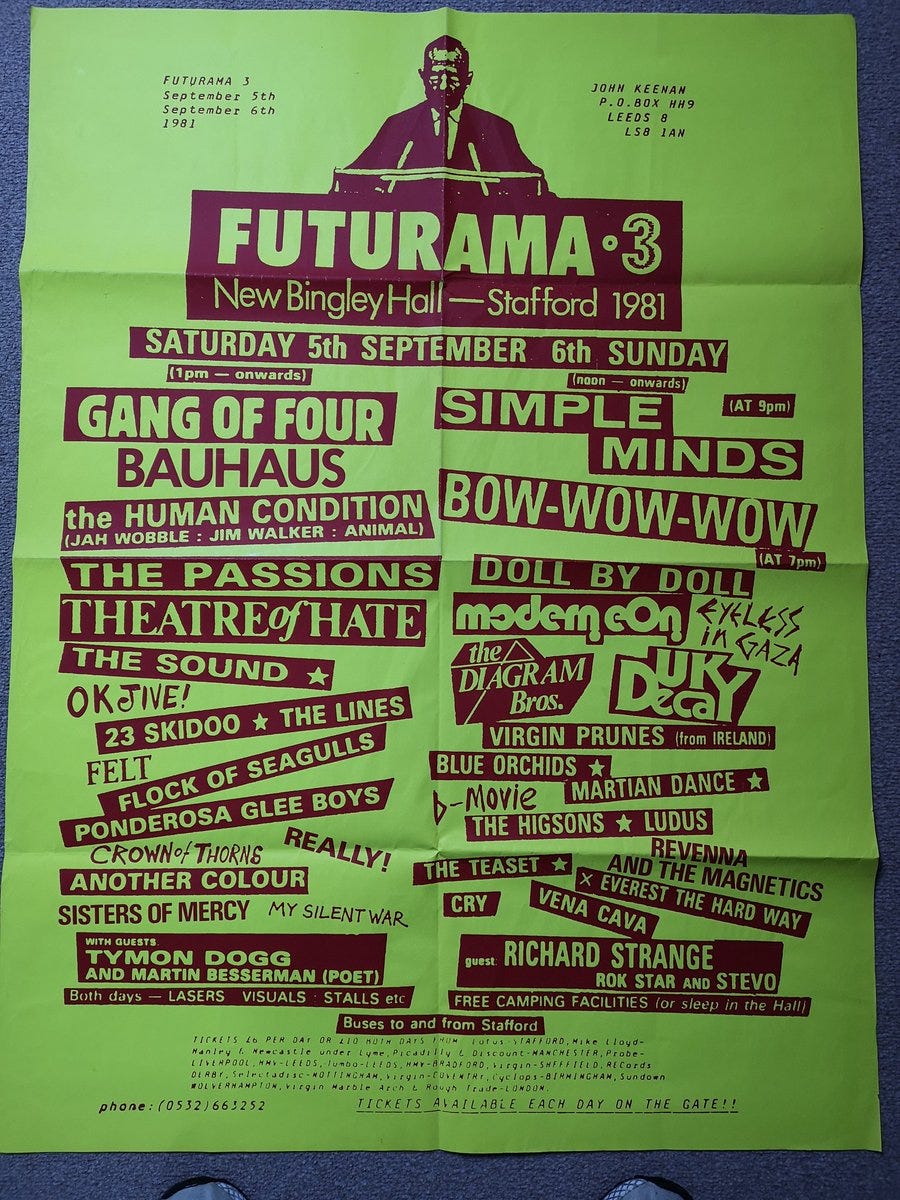

Mmm, but she's an opportunist. She's an egotist. And she's very selfish. They sacked me. And they sacked me because I was getting too many good reviews. And I know that. That and the fact my haircut wasn't quite sharp enough for her. It was very much that. So they sacked me after we did the Futurama Festival21. 10,000 people, we blew 'em away. We were incredible. But the next morning, there was a note, through Richard Boon, the manager's door, saying “We don't want to work with Graham anymore, and there's many reasons” and that was it.

Well it didn't do them much good as a band!

That was the end really for them, to be honest. They sank. We had this great thing. And she sort of threw it away. I've never spoken to her since. I saw them in the street a few weeks later and went over the walk and she hid behind the car so she didn't have to see me. And that was it. Shame. Because I thought there was huge potential there. But then, the right phones started to ring. First it was Dick Witts from The Passage, “Do you want to join The Passage?” Then was someone from Clock DVA, and then it was Alan Wise putting a band together to play behind Nico22: “What do you say?”

And that's already a book in itself23.

Well, maybe a not very accurate one, but yeah.

But again an amazing book.

Yes, absolutely.

It's really interesting running through all that, there's so much continuity of older stuff through post-punk. Did you feel like it was a kind of rewiring of old bohemian ways in terms of the Burroughs stuff, obviously Genesis P-Orridge was picking up the Burroughs stuff. And there was a lot of esoteric stuff going on.

I never went down the sort of esoteric routes myself, particularly, it always seemed a little bit... not bogus, but I mean, there's some pretty unhealthy stuff in there. So I never really went the esoteric route. For me, it was much more primal, you know, getting off on the sort of Velvets’ drone and stuff, and at the same time listening to Fela Kuti, and getting all of that musical stuff. But at the same time, your kind of Burroughs-ian psychology, and obviously Lou Reed tapped into that brilliantly in his lyrics, you know.

Yes, as did Bowie.

As did Bowie, yeah.

Philip Hoare talked about this when we spoke to him: everything in punk and post punk, it presented itself as a rupture with the past, but it’s a total continuation from all that.

Right.

So the Nico experience was obviously a circus in its own right. But how did you feel creatively through that process? Were you fulfilled in it?

Yes. The more I reflect on the Nico time, the more rewarding creatively it was. Because it was fucking chaos. It was a circus. It was madness. It was Gregory Corso climbing into the window to steal heroin, it was all of that stuff. But then sometimes I listen... there's some great recordings, there's a live album that we did in '84 in Tokyo. It stands up, the music's great. Nico, like, much later in my life, David Thomas, had this belief. If she believed in you, she'd let you do your thing. And she believed in me. From the moment we met, we hit it off. I quit numerous times, mostly because of the lack of money and the heroin chaos, and I take the call of [hilariously on-point imitation of the deep husky German accent] “Dids, things are much better, will you come and join us again?” And it would be, and then it would go again. Her timing slipped a lot, but her voice never lost it. She would respond to what you offered. And I was doing Syndrums, gongs, a lot of metallic-y sounds and she just encouraged that like crazy.

Were you doing anything of your own at this time as well, in between?

Yeah, I was starting to dabble with other projects and other things. Sort of halfway through that point, I got contacted by John McKay, and started to work on Zor Gabor with him. And I was starting to do some home experiments with a PortaStudio. But playing with other people as the drummer rather than as the composer was still dominant. And it was a while before I put the drums away to be a composer.

What were you noticing about the landscape around you? Were you picking up on things like the big shininess of 80s pop, or the arrival of electro and hip hop and things like that?

Yeah. Everything. But it's all just going on at the same time as everything else. What I was doing at that time was theatre work, more theatre work. Working with Jacqui Chan, not the Jackie Chan, the other Jacqui Chan, the Chinese dancer from Trinidad, and some people from the London Contemporary Dance. And actually one of the most seminal, and I always forget it, musical experiences I had... in '82, I was invited to go to the Edinburgh Festival as the drummer / sound artist for the African National Congress Choir in Exile. Mind blowing, Mind blowing. Singing those incredible South African harmony songs that had the most radical lyrics you could ever imagine. So I'd say “Well, what's this song about?” “Oh, we will meet you on the streets with bazookas.” It was like that. And I was the only white guy there. They were all South Africans, black South Africans. They took me into their community. They knew... what I have, I have no real technique, but what I have is the ability to channel a vibe. And they realised that I didn't know South African drumming, but I could channel what they wanted because it wasn't just drumming behind the songs, it was a big show with projections and stuff like that. And I'll never forget, I was behind the projection screen in Edinburgh Festival 1982, and we finished the show, your bourgeois Edinburgh people came up and went “Oh, it's so incredible to hear an African drummer” and Andile the choir master just dragged me from behind the screen. “Yep! Here he is.” That was mind blowing. So much going on at the same time, Joe, you know. Next week, I'd be in Berlin with Nico

Tangentially – it's under-reported, I feel, the amount of world music and African music that went into post punk. There was a lot, whether it was Orange Juice or even The Smiths, or whether it was more experimental stuff, it was there as a thread.

Yes, and Nico was very much influenced by the Middle Eastern stuff. Desertshore, and all those things. She played with a lot of Moroccan and Algerian musicians. Obviously, she hung out much earlier with Brian Jones. So she brought that. She was very, very open minded, I suppose, melodically, to that stuff. And her vocal style doesn't have an awful lot to do with traditional...

Western modality. (laughs)

Western modality.

So what was your next move after playing with Nico?

It went on for quite a long time on and off. Then sadly she died. And we had Faction, which was Jim, who wrote the book and myself: we were the basic Faction. So we got the person who was then my partner, Sharon, in as a singer and created a band and made a couple of albums on Third Mind Records. Which was electronic / industrial pop. It was not entirely happy, Jim wanted to be a pop star. Got Dave Formula in to produce the second album. It didn't work. It didn't have the independence, it didn't have the sort of earthiness that we had before Dave got involved, really. We did some touring. Germany, in particular. Third Mind was associated with a lot of industrial music, Front Line Assembly, and people like that. So we played a few of those gigs. We were a fish out of water really. And then I couldn't work with Jim anymore. So I created a duo with Sharon, which became Sonexuno24. It was a great time.

And that was as acid house was hitting.

Yes. Press up a white label. Stick 'em in the back of the car drive to see Nicky Blackmarket, see how many he wants to buy. Yeah. Wonderful. What a scene. Drive to Aberdeen to play a 15 minute PA for 300 quid.

Were you dancing as well?

Oh yeah. I mean, what a scene. So liberating, so exciting. So transcendental.

Can you remember what the first time you saw a dance floor full of “raver” ravers was?

No, I probably can't. I literally can't remember when it started, I suppose really it emerged, in a lot of ways, out of Heaven. In the 80s, they'd do these Monday nights in Heaven, where you'd have Nico, Zor Gabor, or Eric Random And The Bedlamites, weirdo stuff till nine o'clock, then the dance floor took over. You know, so 1987, '88, '89 on the dance floor in Heaven was where I saw that emerge.

Was that Colin Faver25 playing?

It would have been Colin, yeah.

I mean his influence is just...

My god. Colin Faver, Colin Dale, what a pair. Faver was just so radical, what he played.

Well, you know, this is a little before my time, but listening back to mixes and stuff, it just went so smoothly from high energy, industrial, electro, and house just goes plonk right into the middle of it, no seams showing.

No seams showing. Obviously the other connection for me was The Cabs, who were good mates, who were right at the forefront of that transition really. Alongside a few of the other Sheffield groups, I suppose, but primarily The Cabs.

Well, yeah. Mark Brydon26, Chakk. Mark Brydon starting FON.

I worked at FON with him, yeah. And, what was he called? The engineer?

Rob Gordon. Amazing character.

In 1985, we did with Faction, or in '86, we did a Margaret Thatcher cut-up “Listen Buddy”

Oh, yes. I remember hearing it.

Robert produced that.

Excellent.

What a lovely guy.

Amazing guy. Yeah. Just so 100% himself. Yeah. He was one of the first people that we did, when me and Brian started this idea 14 years ago as a blog27. And I was talking to him, and I was like, you're really awkward, but I like you. And I was just trying to locate what it was. And then he started talking about when he produced The Fall. I was like, “Mark E Smith's a bit of a difficult character?” And he was like, “Yeah, no, I loved him.” I was like, “Yes! You're like the Black Mark E Smith!”

Yeah. But he had that softness, didn't he, just expressed in his voice, that Mark E he never had you know.

No definitely, but similar constructive cantankerous.

Ha, yes.

He still does amazing things every so often. I think he's just there in Sheffield tinkering with valves and building sound systems for people's parties and stuff and every so often Toddla T or someone will drag him out to do a gig with Winston or whatever. But he doesn't care, he's not interested in getting feted as a veteran or whatever it might be. He's just doing his thing.

That’s so good to hear.

So you did alright with the rave stuff?

Yeah, I did alright! I got some great opportunities, sold a fair few bootfuls of vinyl. I loved the DIY thing. For me, it was more DIY than punk because it was literally press it up, go to a shop, and you'd walk in, put the needle on the record, first 30 seconds, put the needle on the record halfway through, put the needle on the end. “Yeah, I'll have 20”. So immediate. And they didn't care, you know, they didn't care about “Well does this fit into this? Does this fit into this?” I remember going in with one and, it wasn't Nicky's, it was one of the other West End shops, they had a bit that was called jungle, but they didn't know what to put in it. They knew that jungle was there. But it was like, “What is this jungle? What is jungle?”

That's so funny. Up until, I always put it as '93 when the real splintering happened, but up until that point there were hardcore / jungle DJs playing stuff that now we call trance. It was all over the shop. Nicky Blackmarket was a great mingler of stuff. I mean, he was playing Eat Static and stuff as well. You must have crossed paths with other people from post-punk days and from the festival scene and stuff like that via rave too?

Yeah. And the other thing to throw in there I suppose, for a while at the very end of the 80s I worked with a British pop singer called Bill Pritchard. And he was signed to Play It Again Sam in Belgium, so we came across “French Kiss” and that stuff. Belgian new beat, that was another thing going on at the same time, at that very late 80s stage, that had a big influence.

Fantastically sleazy sound.

Oh my god. Yeah, it's fantastic. I mean, “French Kiss” you hear it today, it's like “Oh my gosh.” You almost blush.

Yeah. Well “French Kiss” was from Chicago. But the Belgians just took that, just that slow sleazy thing from Chicago and Detroit and just went, chugger chugger chugger.

With a bit of Belgian fetishism thrown in.

Guys in goggles and god knows what else. You must have run into people like Youth and Mixmaster Morris?

Yeah. Well I got to know Youth properly quite a lot later. But our path was sort of fluid. I met Youth through Suns Of Arqa, who I did some work with back in the 80s. And then, because of the nature of Suns Of Arqa28, in the 90s, and then in the 2000s, and then the 2010s. And obviously, Youth was always around that scene. Morris was always around that scene. I never actually got to sit down with Youth until probably the 21st century.

Were there any like people within the alternative backroom, electronica-y world that you hit it off with during those early 90s days?

I guess Megatripolis. Can't remember all the names, but that scene really. And there were lots of those little things going on in different parts of the country. West Country, the North and stuff. And I've always liked moving out of the South East because there's so much that goes on in the little corners.

Yeah, definitely. So you were doing your Gagarin thing then?

I started Gagarin in 95. I was doing Sonexuno and we were doing quite a lot of raves.

So that was still for the dance floor, you weren't doing backroom stuff at that point?

No. What happened was I went to Russia. Nick Hobbs organised, I don't know if you've heard of it, Britronica events?

That had Morris and Aphex Twin and...

Everybody. The Orb. Seefeel. Half of Wire. Everybody. Insane. 1993, 1994, Russia, run by the mafia. Nothing organised. Nick thought he would take 30 of Britain's cutting-edge electronica artists over. Chaos ensued. Autechre had their synths stolen by the lighting crew who hadn't been paid. It just went like that. But beyond that, I mean we did a Sonexuno gig with Oakey, in the Velodrome from the Olympics. So somehow, Sonexuno opened the night and then Oakey took over.

What was the crowd like?

They didn't know what to make of it. Because the crowd is a mixture of the kids of Mafia, and a few alternatives. Ours was quite left field, and obviously Oakey was mainstream dance in 1994. Whatever that was….

And alternative in the Eastern Bloc tended to mean industrial and goth really…?

Yeah, very much. So that's what that was. But the other band I went with, which was beyond experimental, called Infidel, was Nick Hobbs' own band, with myself and Keith Moliné, who's the guitarist in Pere Ubu, we got invited to go to the Tabyk shamanist music festival in Yakutsk, which is a nine hour flight east of Moscow, deepest Siberia. The warmest it got was minus 35. But there we came across shamans doing fire ceremonies onstage with throat singing and industrial percussion. And I turned up with a sampler and a drum pad. And it was incredible. Incredible. But the result was I wanted to do a solo project when I came back. Sharon, the singer in Sonexuno, was not a comfortable frontwoman. And I wanted to just do instrumental music. So I came back. I bought these beautiful Russian badges that you used to be able to buy, including one of Gagarin. That retro future thing that Gagarin represented was always a sort of dominant thing in me. So I thought, that's what I'm going to do. I'm going to be Gagarin. So that's what I am.

And have been from then on.

Yeah. Nearly 30 years, 28 years? 27 years. Yeah.

Retro future is such an interesting idea. Because a lot of electronic musicians talk about time travel, and the idea of signals in time29, I mean, you could be Carlo Rovelli and talk about everything existing at all times all the time30 – but the idea of certain sounds sending signals back and forth is really potent.

It is, and it was very there in Russia at that point. Because you had the Velodrome falling down, this futurist building, but wrecked, there was a lot of that deserted, abandoned engineering going on. And Yakutsk was being crushed by the ice, because of the permafrost, and so you've got all of that but then you've got steel tubes floating through the air with the hot water in, and the gas, because everybody had communal heating. It was very, very conscious, I suppose. And, and the sort of Gagarin thing just seemed to create its own journey from there really.

And so that's when you were starting to play in the back room of big electronic events.

Yeah, yeah. Chill out rooms, 3:30 in the morning till 5:30. Yeah, all of that.

Again, did you feel like you'd found your spot, your people, in doing that?

Yeah. I did this thing, I think they called it The Greatest New Year's Eve Party in History or something at Fantasy Island, Skegness. Huge steel dome, 12 arenas, jungle, happy hardcore, house, techno, everything going on at once. And I played the chill out room the next morning. And you could just dip into every dance subculture in half an hour. Derrick Carter, Goldie... you name them, they were there. It was amazing. It was freezing. All the boys were stripped to the waist with steam coming off ‘em. The girls had their belly tops. It was glow sticks and Vicks Sinex, you know?

Very heaven it was in that dawn, to be alive.

Geez, yeah. So I did quite a few of those.

You've done big and small things. Did you ever kind of in your head go “I am pursuing an underground route” or think “Actually, I would grab bigger success if it came” or anything like that?

Yeah, the underground route really. You know, if somebody had come along and said “film soundtrack this”, I would have taken it. But I wasn't trying to make bangers for the dance floor, I was just following what felt for me the most natural furrow, which was underground really. And I think because of my age, I didn't have that ambition to be a pop star, because, you know, I started Gagarin at 40.

And were you able to make a living from your own music then, through the next few years?

No.

No. Were you making a living as a musician in genera.?

I started to be a community musician at that time, and that's where most of my income was coming in, and has continued to come in ever since really. I was doing the odd session, I'd do the odd thing like that. But fundamentally, more money came from the community music than the performing.

So what would that involve?

Well, initially, I got into community music, my job, my role, through music technology. Because when I became a community musician in the mid 90s, no one else was doing music tech. Obviously, not only did I know music tech, I knew the music the youth wanted to make. And as you know, a little later I had the incredible experience of being involved as garage moved into grime eventually. For years I would be in youth centres, pupil referral units, crime prevention units, working with predominantly black youth, doing rap, programming beats. I suppose when it started it was more hip hop really. And then, you know what the British are, they wanted their own music. you know, It came through house and garage you know. And UKG is what it became really, speed garage. There was a move from d'n'b, some of them were doing d'n'b, but the challenge for d'n'b for a spitter is that your lyrical flow is really musical, not so lyrical. Because “Skibby-dibby-dibbetty”, all that stuff, and you can't say a lot and really be heard. And I think also d'n'b, on a dance floor, wasn't as accessible for women, to be honest. It was a very male dance floor. It was an exciting dancefloor, it was a dynamic dancefloor. But then slowing the beats down a bit, via this thing called speed garage, to what became UKG, and then what became for me possibly one of the most exciting musical movements for the last 50 years, as grime emerged really, around the beginning of the 21st century.

It was so, I don't know. Being very much an outsider to it, but going into London on a regular basis and then just getting in a taxi, hearing the radio, hearing what was coming out of every car, it was so sudden, it felt that everything had coagulated in a way that made sense but could never have been predicted.

Yes. thought musically it was incredibly exciting. Because I like angular beats, I've never been great at four on the floor myself. I love the angular beats and I love the atonality. There's a story I share when I'm doing training and stuff, there was a lad and he was making a beat and he had two very tight semitones creating this very atonal sound. And I wanted to find out was that an intention? So I said “Is that what you want?”, or I turned it into a major chord. And he said, “That's what I want.” And I said, “Why?” “Because that's what my life sounds like.” These guys were making conscious decisions about how their world sounded, and how their world felt, and expressing that sonically as well as lyrically.

Absolutely. And I think there was such a myth that because maybe one or two beats had been made, probably for a laugh, on a PlayStation, that it was all unschooled. And it wasn't so many people were coming into that from drum and bass, there were plenty of studios, Wiley and everyone had already had their experience with garage. One of my favourite proto-grime stories is that “Champagne Dance” by Pay as U Go Cartel, Matthew Herbert plays keyboards on it, because he was in the studio next door, and the engineer was like, “Oh, this could do with a nice little jazzy keyboard lick. Matthew’s next door.” Got him to come in. So Herbert and Wiley are on the same track,

That's amazing. And those kids, they were so welcoming. For me, the welcome was largely initially based on the fact that I could programme hi-hats that they couldn't dream of programming. “Man, Sir can program the hi-hats!”, so that opened the doors and then I'd get these messages on MySpace from these guys, “Wag1?”, spelled with a “1”. They were just so welcoming, whatever their crews were, they listened to me, they responded to me. So that, for me, was the first half of my community music. And then I got a little tired of Pupil Referral Unit, crime context, I suppose. And moved more into the disability, neuro disability, neuro difference, back to free improvisation. And really, for the last 10, 15 years, my work has been dominated by sitting in a room with a bunch of very neuro diverse people improvising. That's what I do. And I get very well paid for it. And I'm very good at it. And it's incredibly rewarding. Because free improvisation takes away all the barriers. When you can’t communicate in a conventional way you express, and I have seen communications between a severely learning disabled pair of musicians that compare with the highest level of free improvisation I've seen in Cafe Oto or anywhere else. There's just no doubt. And for me, what was so organic about that is joining Pere Ubu31, and doing a lot of free improv. So Saturday night, we'd be playing to 500 people doing a weirdo improv set. Monday morning, I'm doing exactly the same shit on the floor with a bunch of learning disabled kids.

It must make you look back over musicians you've worked with in the past, because we all know now how many people within music are neurodivergent and plopped together because they were. So you must kind of map out your head differently a lot of the things that you've experienced in the past?

Absolutely. Because we didn't know. We didn't know. You know, why do people want to make drone? Why do people want to make sequence-y music? What are they looking for in this? What is the prompt, and it's like, oh, you're autistic, you're autistic, you're autistic, and it just now makes sense. And I'm about as un-autistic as it's possible to be, weirdly, but actually, I think that's made me able to facilitate and because I'm not autistic, but I get drone, I get sustain, I get all of that stuff, and it's remarkable, but it is incredible how nearly everybody, especially in the modular synth world, I mean, they're all autistic.

And different neurotypes have their place – you know, ADHD, the hyperfocus, whatever...

I do have ADHD.

Yeah, I do. I mean, I’m waiting for the final diagnosis to be signed off, but you know, look at the state of my shelves [gestures around].

Yeah I mean, look at the state of my studio, but if you wanted me to find an XLR to jack....

Yeah, hyperfocus kicks in. And you realise that the communication between the different types of neurodiversity creates the dynamics, creates creative dynamics, creates group minds among scenes, pathological demand avoidance is a new one to me. So it's a flavour of autism. So I'm sure you've noticed…

Especially with the girls.

Especially with the girls, and suddenly, I hear a PDA kid speaking and I hear John Lydon's voice. And you're like, that's what John Lydon is, that's what John Lydon is an avatar for, you know? Punk is demand avoidance, right?

Yes, absolutely. Because ADHD didn't exist when I was young, obviously. And I've developed a negotiation with it, and a way of navigating and operating the world with it. I can come into the studio, and I can get focused in 30 seconds. I don't need to do all of this to get in the zone. So I can do half an hour, and then I can go and do half an hour of Goldsmiths marking, and then I could do half an hour in the garden, then I can come back and go straight into it. And that's made me quite effective and quite efficient in a world that really isn't suited to that kind of mentality.

Yeah, there is so much to be written about coping mechanisms and how they, again, parlay into things that we know as cultural. There are coping mechanisms that have become in themselves little cultural patterns or ways of being. On the how we interact with each other thing, I remember, I did a discussion thing. You must know Nwando Ebizie, have you seen her? She's amazing. She's from the Peak District I think, she does installations, dance, vocal stuff, she's very into storytelling, Yoruba and Igbo mythology, everything all at once. She did this amazing installation in Manchester32, she has this mental condition that causes visual snow, visual distortions. So she built this installation that's like the best chill out room you've ever been in with gauze and projections of speckles and lights and stars. And it was to show you what it's like being in her brain, but at the same time, she created this beautiful space. And then she sat in it, and she had these girls in white robes who would feed people honey and honey cakes and milk, and then she would tell stories and have discussions within this space. Fantastic artwork. And she got me and a neuroscientist, and I've forgotten who else, to have a fully freeform conversation in this space with these people around us being fed milk and honey. And obviously neurodivergence was part of the topic. And we started talking about who you gravitate to, and I just realised that, you look back at the groups of mates you go raving with or whatever, and it was like “Avengers Assemble”. It was like, Marvel specifically, superheroes, flawed people, each with their own special ability. And they could come together to kind of vaguely function together. Not to romanticise neurodivergence, but the way clusters of people fall together is subculture in a sense.

I mean, I'm jealous. I was just a bit old for that. The free festival scene represented that to some extent, 20 years earlier really.

And in terms of where you inhabit musically through the 20th, 21st century, it has been more or less the experimental world. Cafe Oto, small tents in festivals, that kind of thing. And that's been comfortable for you.

That's my world. Yeah.

And you've got lots of friends from The Wire Magazine type world. I've rarely got time to go off on those things, but if you’re full time in the Wire world, it’s totally possible you see the same people every weekend in Oslo, and Krakow and, and wherever, it's a real social network.

It is. I don't feel I've ever been accepted into The Wire world very much, fully.

Well, not specifically The Wire but experimental music internationally.

Yeah. Obviously being in Pere Ubu has opened a lot of those doors, because Pere Ubu is an avant-garage rock band, but it's not. It's an avant-garde thing, whatever it is. And so yeah, we've played all of those festivals everywhere. Continually. And the great thing about doing it in Ubu is you're playing to 500 people, not five people.

Yeah. And in terms of meeting people and seeing other acts and stuff. I mean, do you feel that there is like a global, I don't want to say family, but you know, a social entity around all that stuff?

Yeah, there is. People have stuff in common, even if they've never met before. And you're very, very, very quickly bond. I mean, we met People Like Us33 last year. Never met them before. 20 minutes later, it's like you've known them for 20 years.

Yes, of course, anyone like that. I don't know if I've met them in the flesh, certainly been in the same room. But because they're from Brighton and they're friends with Semiconductor, Ruth and Joe34, you know, straight away, I could walk into a conversation and go in the same way.

Yeah, and that's bloody great. You know, not everybody's got the same... we've been discussing my lineage and my touch points. Obviously some of these people are younger, some of them are more academic focused. Some of them probably haven't, you know, sat and smoked half an ounce of weed listening to King Tubby as I have, but we've got plenty in common.

It's a good place to be. Well, you know, typically at this point I would ask about the future, but that is very much unwritten obviously.

It's very much unwritten. I mean, you know, my new album, Komorebi. I knew I had cancer when I started to make the album. I had a few of the tracks lying around from other projects, especially the project on top of Box Hill last summer. And I thought, I will do this while I'm doing chemotherapy. And I sat in this space, and I sat in this space every day, I set myself a deadline. As always, I give myself a week on the deadline, but only a week. I finished the album on the deadline, within the week's deadline. I knew it was complete. It captured what I wanted to capture. Whatever that is. When I listen back to now it seems so uplifting.

It is a beautiful record. And funny you mentioned right at the beginning, Britten and Vaughn Williams because that's in there.

Yeah, you know that. I've used three notes from Vaughn Williams. One of the pieces that was commissioned for the top of Surrey Hills was to come out of Lark Ascending. So the first three notes on a piece called “Wonderdusk 1” are lifted from “Lark Ascending”. And there's other folk melodies in there too. Yeah. I love the pastoral stuff. Still do. My last but one gig was in a willow dome on Stanmer Park outside Brighton. Week before last. Fucking gorgeous. They're building this thing they called the Eco Musicology Park up there. Spirit Of Gravity kind of Brightonistas are building this thing there. Doing amazing work.

Oh, wow. I'm gonna check that out then. Fantastic. Well, you know, it's, it's amazing to see you enjoying these gigs as they come.

I've done 11 in four months, I've got a live stream in two weeks tomorrow. So that's good, because I know I can do that. I just sit in here and livestream for an hour. I feel once I get the brain under control that I will be able to get back to it. I'm supposed to be doing a live soundtrack of the Nico film in June in Manchester35. That's a target. It may be a target too soon, but I hope not. And I've also got a project to do duos, with loads of the great musicians I know. So mostly, I'm doing what I'm calling seeds. I'm creating little one minute bites that I'm sending to them to respond to, and build on that from that, but then I'll probably also get a couple of people down, maybe Keith Moliné, maybe Alex Ward36, maybe Mark Beasley37, to come and actually improv together in the room here.

Fantastic. Oh, well, it’s just great to see you keep on keeping on Graham.

You can't stop Joe. What are you gonna do? I just need to make sure the files don't get lost in case I go before they’re finished.

Don't let the ADHD get the better of your file systems.

My favourite thing in the world is Apple-F. Actually, no Apple-Z is probably even better.

Yeah, yeah. Wow. There's a whole cultural history to be written about the invention of undo. It's the opposite of improv, right?

You know, there's many times in my life I wish I could do undo. Especially right now, but you can't.

Well, no regrets.

No regrets, no regrets. The great thing to coming, as I may be, towards the end, is I literally have no regrets. I have no bucket list. I have nothing frustrating me. I just want to do a bit more. But that's all, you know. So what can you say? I've lived an incredibly exciting, creative, rewarding life. I'm 69. I wanted to make 80. I'm not gonna make 80 But if I was asked when I was 16, what would you want to do? I've done it.

Well, here's to making 70 anyway Graham.

70 on August the 1st. Hopefully a west coast road trip in Scotland is the plan.

Honestly it’s impossible to overstate how great their work together is - their two albums and various EPs are all essential.

In a Bandcamp Daily review, I said: “On this new album, he seems fresher than ever, creating epic high-tech landscapes out of the sonic languages of UK rave and grime and Detroit techno—especially the stirring synth strings of classic Carl Craig—but lacing them all with nature sounds and lyrical, pastoral motifs.”

Hubbard founded the Church of Scientology in Saint Hill Manor, East Grinstead - a stately home he had bought from the Maharaha of Jaipur - and it remains the church’s UK HQ to this day. Tom Cruise has a house right nearby - dubstep godfather and super DJ Artwork pointed out to me when I went to make cider with him once, true story that.

AKA Mormons.

Steiner Schools are considered fairly “mainstream alternative” now, but their founder Rudolf Steiner was a weirdo of staggering proportions and the organisation that built up around him very cult-like.

Congregational churches are considered self-governing, not beholden to a diocese - like the Quakers, they were part of the British dissenting tradition which often drove radical politics.

Thatcher cited the Joe Meek-produced “Telstar” as her favourite record in interviews with Smash Hits and Desert Island Discs.

The supergroup put together around Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson of the BBC Radiophonic workshop, which made the wonderfully peculiar and occasionally saucy album An Electric Storm in 1969.

British jazzer Malcolm Cecil and American producer Robert Margouleff created TONTO (The Original New Timbral Orchestra), a room sized synth which they made one glorious proto-ambient album on and provided sonic weirdness for Stevie Wonder in his imperial phase.

A set of children’s stories on record released from 1947 on which used sound effects and vocal processing.

Singer with The Deviants, journalist, author of Give the Anarchist a Cigarette, lynchpin of the West London squatting scene (see in particular the Youth chapter of Bass, Mids, Tops for more on that), and all round groovy fucker

.

Of the Southeast London Abbey Wood chapter of the White Panthers, who took the radicalism of the Black Panthers as a cue to set up free food programmes and various kinds of community activism.

John McKay would found Zoe Gabor in the mid 80s - see later on.

Dowdall got a law degree and worked for a community law firm providing representation particularly to young people of colour victimised by police.

Painter, performer, poet, writer, mystic, rogue, confidant of Burroughs and co-devisor of the cut-up technique, inventor of the Brain Machine, etc etc

.

It was Burroughs, and the correct quote is “When you cut into the present, the future leaks out” - that is, if you chop up and rearrange the media of now, indications of what’s to come might be revealed.

On Joy Division’s records - joining some dots, as has been pointed out, his studio technique was “pretty similar to dub and Joe Meek”!

Indeed a lot of people from the goth-electropop-industrial culture that was nurtured in the Batcave club would go on to be major players in the Goa trance scene which Youth would also join up with.

Songs They Never Play on the Radio by Dowdall’s then bandmate James Young. For all that there is some questionable recollection, it remains one of the most beautifully written portraits of musical life on the fringes.

Their stuff is still rightly sought after, and I’m actually kicking myself I didn’t include it in my recent roundup of psychedelic rave as it fits right in.

An unbelievably important bridge from postpunk into rave, UK techno and beyond.

Mark Brydon of industrial funk band Chakk built the FON Studios, was behind some very early UK house, and most famously went on to form Moloko with Róisín Murphy.

Extraordinary collective and early Adrian Sherwood collaborators, centred around Manchester based Michael Wadada - SoA had over 200 members over the years.

I was thinking of Cristian Vogel’s Station 55 and Coil’s Time Machines here.

Pretty sure that’s not actually what Rovelli thinks, but the psychedelic physicist does have some mind-frying conceptions of what time is… (I’m convinced his “light cones” were the influence for the hourglass emblem of the Time Variance Authority in Loki but that’s another story)

Dowdall joined Pere Ubu in the early 2010s, backing up the elemental force that is David Thomas, and has been a permanent member ever since.

Here’s a later iteration of the installation piece in Brighton, it’s constantly evolving - I also got the chance to DJ inside the installation when it was in East London a little later, which was total joy. Ebizie’s work is always worth checking.

The collage project of artist Vicki Bennett.

Science/art experimental musicians and filmmakers… Who as part of Disastronaut I once shared a split LP with.

On the 15th. It’s Nina Danino’s experimental Solitude, originally released in 2022, trailer here:

Multi-instrumentalist improviser and occasional Pere Ubu collaborator.